Industry

Highlights

- The path to electrification may not be as straightforward as was once imagined, with one of the more prominent challenges being the charging infrastructure.

- The answer to the charging conundrum does not lie in the resolution of the infrastructure availability problem alone.

- What the EV industry needs are ‘ecosystems that grow’ – a transition from fragmented, infrastructure-heavy charging networks to adaptive, intelligent, and self-sustaining ecosystems.

On this page

The age of the electric vehicle

The explosive growth of EV adoption following the COVID-19 pandemic years, particularly in China, Europe, and the United States, has established it as a clear sign of the times.

Backed by policy and incentives, there has been a veritable shift in adoption trends causing EV market share to rise from 4% in 2020 to 18% in 2024. Nearly one in five new cars sold is expected to be electric, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

This has been in line with the strategic commitments of major automakers who announced that they would convert a substantial proportion of their portfolio to EVs over the decade. However, the recent slowdown in adoption underscores a fundamental challenge: charging infrastructure must scale at an unprecedented rate to support this transition.

The charging conundrum

There is no doubt that the future of sustainable mobility will involve a significant mandate for electrification.

However, it is also clear that the path to electrification may not be as straightforward as was once imagined, with one of the more prominent challenges being the charging infrastructure. This challenge is now evident in the strategic shifts of multiple automakers, who have begun reintroducing hybrid vehicles into their portfolios alongside battery electric vehicles (BEVs). This pivot is essentially driven by the combination of an aspirational transition to sustainable mobility alternatives, with the reluctance to commit to an all-electric alternative without reliable charging infrastructure.

But the calculus of lifetime CO2 emissions can be complicated depending on how often the hybrid’s gasoline engine is used. A hybrid could potentially be cleaner than an EV, given its smaller manufacturing footprint, but only if its gasoline component is used sparingly. Therefore, hybrids offer a short-term bridge to full electrification, but they do not eliminate the need for robust charging networks.

According to the TCS Future-Ready eMobility Study 2025, charging remains one of the most decisive factors for consumers considering an EV purchase,

66% of surveyed consumers cited charging time, and 60% cited charging infrastructure availability as key concerns affecting their purchase decisions. Only vehicle cost (including maintenance) was ranked higher in importance, by 70% of surveyed consumers.

Automotive original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) also identify charging infrastructure compatibility as a top priority, with only a minority (35%) expressing satisfaction with the current level of collaboration among stakeholders in the EV infrastructure ecosystem. This has reinforced the need of the advancement of the charging ecosystem to drive the success of EV adoption.

The demand for a strong and expandable charging network is at an all-time high. According to the European Commission, an estimated 3.5 million public charging points must be installed by 2030 to meet the market demand. However, reaching this target requires deploying 410,000 charging points annually which amounts to a rate that is almost three times the current annual installation rate.

Meanwhile, the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) projects that the real requirement is closer to 8.8 million chargers by 2030—a significantly larger goal that would necessitate installing over 22,000 chargers per week, an eightfold increase over today’s rate.

The solution to the charging conundrum cannot be one dimensional. The transition from the current fragmented and inefficient network to an optimized system that can support the demand of the EV mandate requires coordinated evolution across five critical elements:

- Energy generation and supply

- Charging infrastructure

- Grid integration and management

- Charging experience

- Business models

Optimizing supply and demand

The energy supply layer is the veritable backbone of the EV ecosystem.

The electricity that is used to charge EVs on the road today comes from local electricity networks. There are two implications here. Firstly, the sustainability quotient of EVs is only as good as the source they derive electricity from. Secondly, with the rising adoption of EVs, the electricity grid needs to be able to absorb the additional demand.

The good news is that power grids across the world are being integrated with Renewable Energy Sources (RES). For e.g., The National Grid, the electric power transmission network for Great Britain currently records a higher share of renewables and nuclear power sources contributing to electricity on the grid, over fossil fuels which contributes around 26%. Germany, Denmark and other European countries are seeing record contributions of wind energy as a source for electricity generation, outstripping coal.

The energy transition to renewable sources can potentially overcome the long-held criticism of EVs that they reduce tail pipe emissions to the detriment of emissions at source. However, RES integration into the power grid has two major challenges, which are:

Grid capacity and network constraints: The best places to harness renewable sources of energy like wind and solar are not close to the areas of demand, for example, cities where power is needed. The grid does not have the capacity to move large amounts of energy from these locations to where people need them.

Network management: Conventional power grids were never designed for fluctuating energy sources like wind and solar. Power fluctuations increase with the share of RES in the grid, and in the absence of real-time network management, can cause voltage instability, damage to equipment due to harmonic distortions, and even blackouts.

Sustainable energy transition therefore requires an overhaul of the grid. ‘Energiewende’, Germany’s ambitious energy transition initiative seeks to reduce reliance on its baseload power plants through an innovative mix of advanced forecasting for renewable energy, responsive control systems that adjust electricity flows in real time, battery storage systems and the large-scale addition of transmission lines. AI-driven forecasting, demand-side response mechanisms, and IoT-enabled grid intelligence will play a critical role in stabilizing fluctuating power supply and demand.

On the demand side of the energy ecosystem, EV charging stations have grown and evolved significantly in the last couple of years. Europe, for e.g., has recently crossed a million public charging points, from only 100,000 in 7 years. The US too has been seeing a significant uptick in this area with 200,000 public charging points with 9,000 installations in as little as seven weeks.

However, the answer to the charging conundrum does not lie in the resolution of the infrastructure availability problem alone. To match up to its equivalent in the internal combustion engine (ICE) era, systemic differences in how the infrastructure is set up need to be accounted for. For example, fuel stations have always stored fuel on site; EV chargers rely on real-time grid power. With increased usage, charging stations face a risk to grid load and stability, a consideration that was non-existent with ICE vehicles. Fuel stations don’t suffer from an interoperability problem; with EV charging, different connectors, networks and payment systems create a fragmented system.

The adoption of the industry standard Open Charge Point Protocol (OCPP) has allowed EV charge points and charging station networks to communicate seamlessly, enabling network flexibility for the charge point operator. With the much-anticipated universal Plug & Charge (ISO 15118) protocol scheduled for implementation in 2025, mobility consumers will be able to have their charging sessions securely authenticated and paid automatically in any charging station. These measures will go a long way to solving the interoperability problem. However, this transition requires significant infrastructure upgrades, and full interoperability remains a work in progress as networks phase in these updates across different regions.

Unlike fuel stations that require designated pockets of land, EV chargers must also be embedded within existing urban infrastructure - residential and commercial buildings, each with their own regulatory, logistical and operational constraints. This poses a significant real-estate challenge even as urban planners look to integrate transit-oriented development into city planning.

Startups like ChargeArm have tried to solve one such challenge associated with the lack of space for home charging in countries like the UK and Netherlands, the problem of EV ‘cable over the pavement’. By using an arm extending over the pavement, it offers a clean and safe charging solution that complies with regulations.

Optimizing charging experiences

The human aspect of charging- the user experience, is equally crucial to EV adoption.

While expanding station availability reduces range anxiety, charging points must be easily accessible, user-friendly, and integrated with their mobility journeys. Charging discovery, slot scheduling, and payments must be seamless—preferably consolidated under a single digital interface that allows users to locate chargers, check availability, and process transactions in real-time. The transition to Plug & Charge aims to eliminate these frictions, but until universal adoption, ecosystem-wide collaboration between charge-point operators (CPOs), e-mobility service providers (eMSPs), grid and utility providers, digital platforms and OEMs remains essential to a seamless charging experience.

Charging downtime itself is also evolving from an inconvenience to an opportunity. Starbucks, in collaboration with Volvo and ChargePoint, has installed fast chargers at its stores, transforming charging stops into premium retail experiences. Similarly, major hotel chains such as Hilton, Marriott, and Radisson are integrating charging into their hospitality offerings, partnering with OEMs, CPOs and eMSPs, recognizing that charging is no longer a standalone service, but part of a holistic customer journey.

Economic models for charging

Charging is also becoming a profitable revenue model on its own, as many retailers like Walmart have come to realize.

Ecosystem collaboration will only increase the economic potential of this revenue stream, while EV adoption accelerates. Ride-hailing company, Uber has partnered with BYD to introduce EV-specific incentives to lower the total cost of ownership for drivers, accelerating EV adoption in commercial mobility. Real estate-driven models such as those followed by companies like It’s Electric leverage existing urban infrastructure to host public chargers, creating passive income opportunities for property owners.

Bi-directional charging on the other hand is creating a monetization opportunity for mobility consumers, while also serving as an energy source for the grid. Duke Energy’s initiative to compensate Ford F-150 Lightning owners for feeding energy back into the grid exemplifies how EVs are shifting from passive assets to monetizable energy resources. This model not only reduces ownership costs for consumers but also enhances grid stability by utilizing EV batteries as distributed storage units.

Building charging ecosystems that grow

Infrastructure cannot solve the charging conundrum on its own.

The integration of these five elements—energy supply, charging infrastructure, grid management, customer experience, and business models—is essential to creating a charging ecosystem that is resilient, self-sustaining, and capable of supporting the mass adoption of EVs.

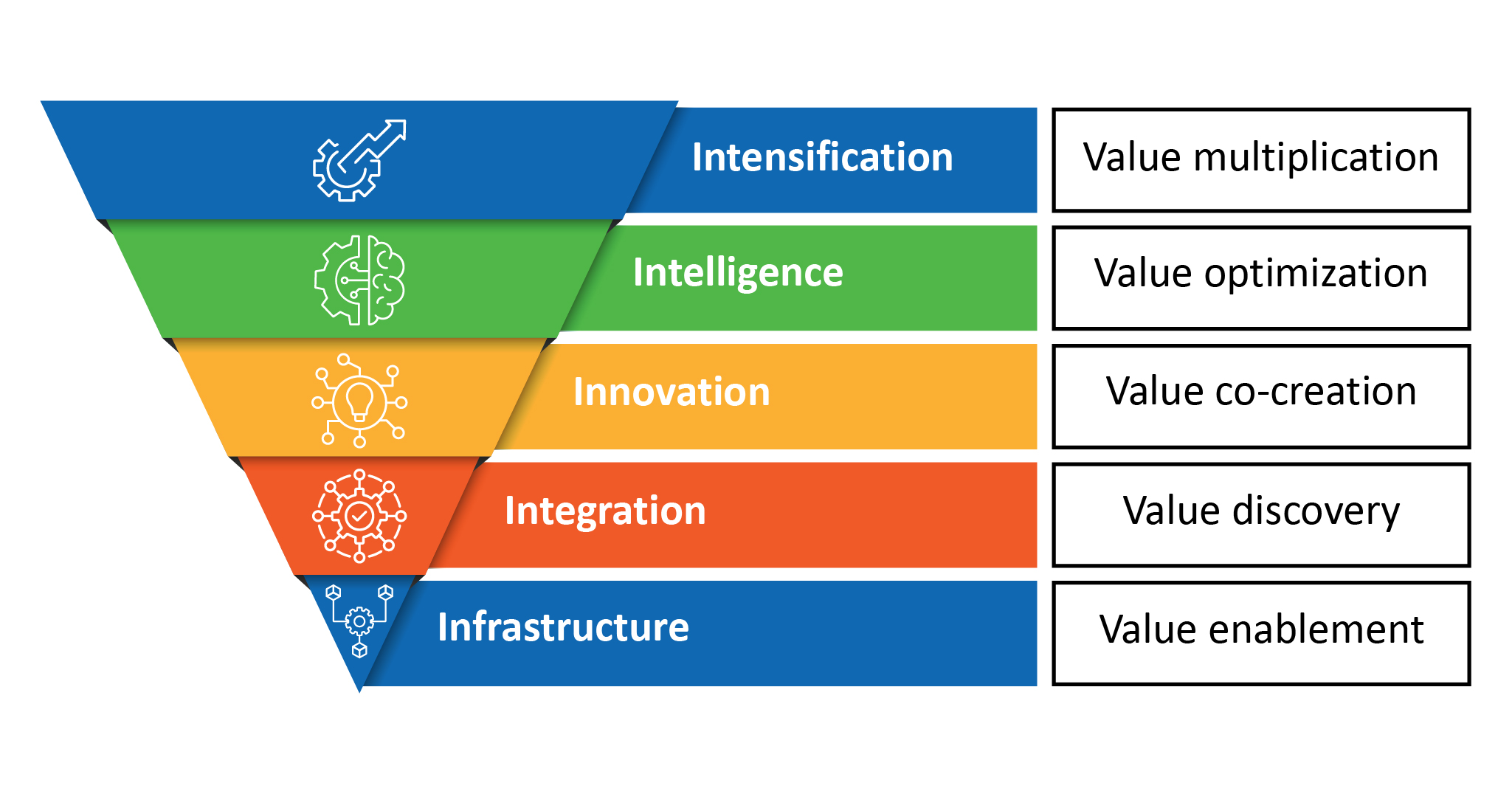

Vijay Govindarajan et al, in Harvard Business Review, introduced the concept of ‘products that grow’, emphasizing how products adapt and change to suit users’ evolving needs. We have conceptualized the ‘ecosystems that grow’ (ETG) framework, which espouses that ecosystem sustainability will depend on mutualistic relationships where participants actively enable one another’s success and growth. While this framework can be extended to any business ecosystem, we have used it here to develop ‘mobility ecosystems that grow’ (MEG).

The framework is built on five interconnected layers (see Figure 1), each progressively enabling the ecosystem to scale, innovate, optimize, and expand. While not entirely mutually exclusive, these layers provide a structured approach to ecosystem growth.

Infrastructure (Value enablement)

At the foundation of every ecosystem is the need to define who participates and what infrastructure is required. This involves identifying core players (such as utilities, OEMs, CPOs, and eMSPs) and establishing the physical, digital, and regulatory infrastructure necessary for transactions to take place. The goal at this stage is to create a minimum viable ecosystem (MVE)—a baseline system where a functional value exchange can occur before scaling further.

A critical metric here is the degrees of freedom (DOF) which is defined as the number of value creation connections each participant in the ecosystem can form. For a charging ecosystem to expand, each participant must see their degrees of freedom (DOF) increasing—not just in technical interoperability, but in economic and strategic value creation. Without this, the ecosystem remains stagnant, even if infrastructure expands.

Integration (Value discovery)

Infrastructure alone does not create a viable ecosystem. Participants must move beyond transactions and data-sharing agreements to deeply aligned partnerships and a self-reinforcing reason to collaborate and grow. Mutualistic value is not realized in a business ecosystem because of a misalignment of incentives between participants. This is where the value integrator (VI) emerges as a key role. The VI can be an agency within the orchestrator organization or an independent entity that ensures value is created, exchanged, and scaled for all participants. The primary role for the VI is to engage in value discovery to ensure that infrastructure investments and incentives are aligned with end outcomes. At this stage, the ecosystem must:

- Align incentives to ensure long-term mutualistic partnerships.

- Establish platforms, connectors, and governance mechanisms that can evolve dynamically

- Ensure that value exchange remains optimized over time.

For a collaborative charging ecosystem, this means ensuring that utilities, OEMs, CPOs, and eMSPs are not just interoperable but incentivized to work together—through dynamic pricing models, shared revenue streams, and data-sharing platforms.

Innovation (Value co-creation)

As an MVE matures, participants can begin leveraging shared data to create new value propositions. New use cases must emerge from the initial set of transactions and customer journeys. However, ecosystem dynamics often lock players into their initial value models. Breaking this cycle requires structured co-innovation, a process that can be enabled by the VI.

For example, a fragmented set of charging apps could evolve into an open-access charging platform where revenue-sharing enables all stakeholders to co-exist and co-create. This will require charging networks to be integrated with universal standards and standardized pricing models, while also opening opportunities for revenue creation like advertising on digital signages at EV chargers.

Transport for London’s (TFL) open data ecosystem is a great example of how making data accessible and transparent can enable new products and services to help mobility customers.

Intelligence (Value optimization)

Ecosystems cannot expand at the cost of efficiency. While this layer can occur in tandem with value co-creation, this layer involves leveraging AI, automation and data driven decision making to optimize ecosystem efficiency. This layer is important for the ecosystem to lower costs and maximize resource utilization.

Generative AI and agentic AI become powerful enablers at this stage. Conventional mobility journeys did not involve a high-touch engagement between mobility service providers and OEMs. GenAI can enable a conversational platform for the customer to have an ongoing engagement with the mobility service provider and a mechanism to have hyper-personalized services curated for them, while agentic AI can automate workflows and business decisions. For example, a charging network can adjust prices dynamically based on demand ensuring optimal charger usage while and AI powered fleet management system (FMS) can schedule vehicles for charging and maintenance based on real time battery parameters and the demand on the network. The use of computer vision by California based startup Juice, on DC fast chargers enables a user’s EV identification, charging session and payments without apps or physical payment devices, partially solving an interoperability problem

Intensification (Value multiplication)

The ecosystem achieves a stage of ‘value equilibrium’ – where core participants are effectively integrated, AI driven optimization has enabled ecosystem efficiencies, and mutualistic value is being realized by incumbents. The focus of the ecosystem then shifts to expansion by integrating new industry participants, emergent technology and business models. The VI again plays a key role—deciding which partnerships add value without destabilizing the system. For the collaborative charging ecosystem, intensification might include expansion into retail, hospitality, logistics and real estate. Charging stations can become potential energy hubs that generate their own power through RESs and trade excess energy in a peer-to-peer energy marketplace. It can enable bi-directional charging by collaborating with parking lots to support grid resilience while enabling customers to monetize their EVs.

The EV ecosystem is rapidly evolving, but constraints on grids, hardware, software, and business models threaten its scalability. The ‘ecosystems that grow’ framework can enable the industry to transition from fragmented, infrastructure-heavy networks to adaptive, intelligent, and self-sustaining ecosystems