Conventional reports

Analyzing clinical trial data culminates in tables, listings, and figures (TLF) as reports that are part of the clinical study report submitted to regulatory authorities or can be used for an ongoing review during study conduct e.g., safety update reviews. The importance of accuracy with respect to content makes it a time-consuming, effort-taking but necessary activity for clinical study analysis.

Clinical data reporting

There are two aspects of clinical reporting:

Designing the TLFs, and

Generating the TLFs based on study data

Both activities are manual, and interrelated but can be catered for by a single solution. Let us understand this further.

Designing clinical trial report

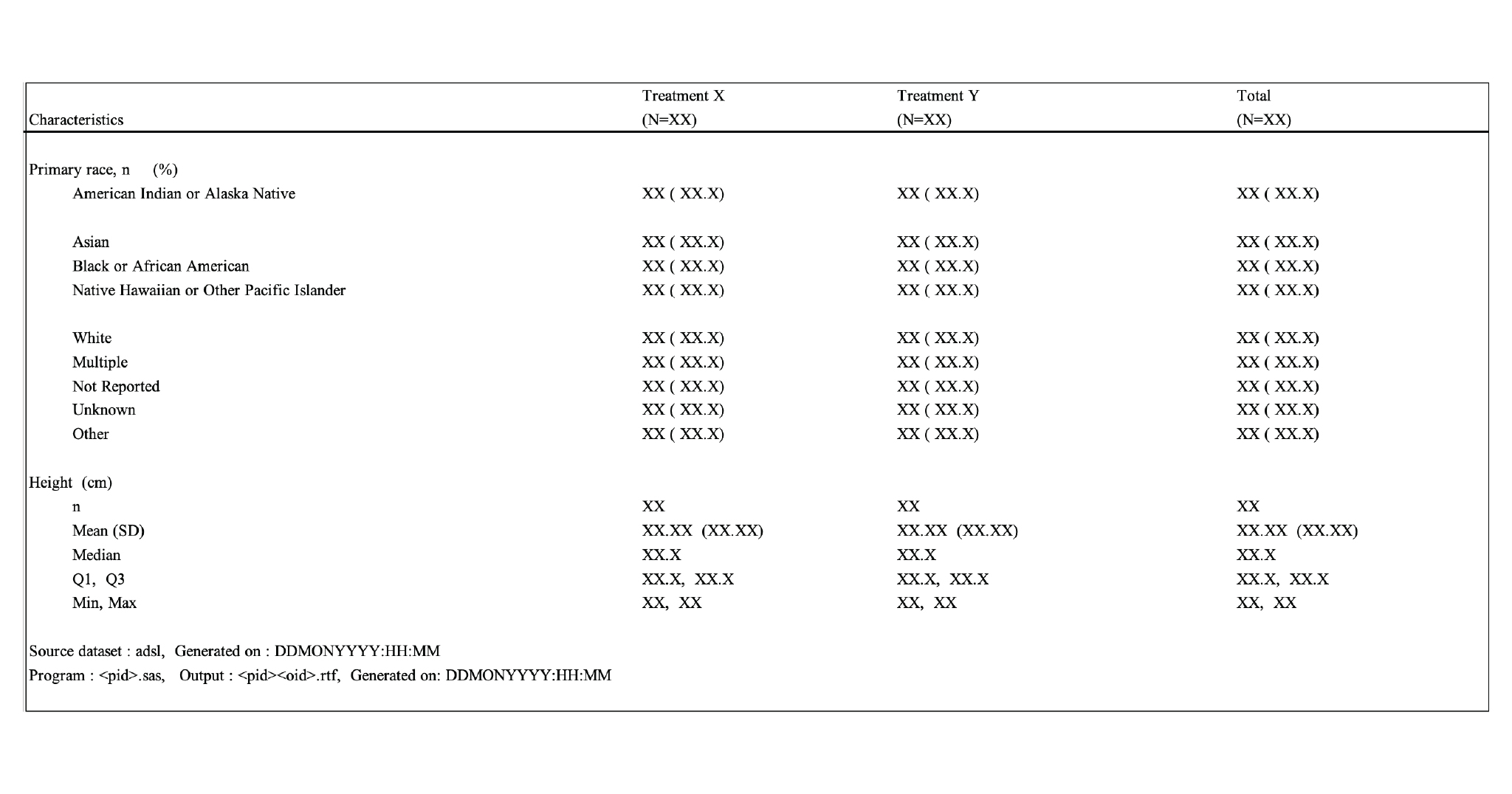

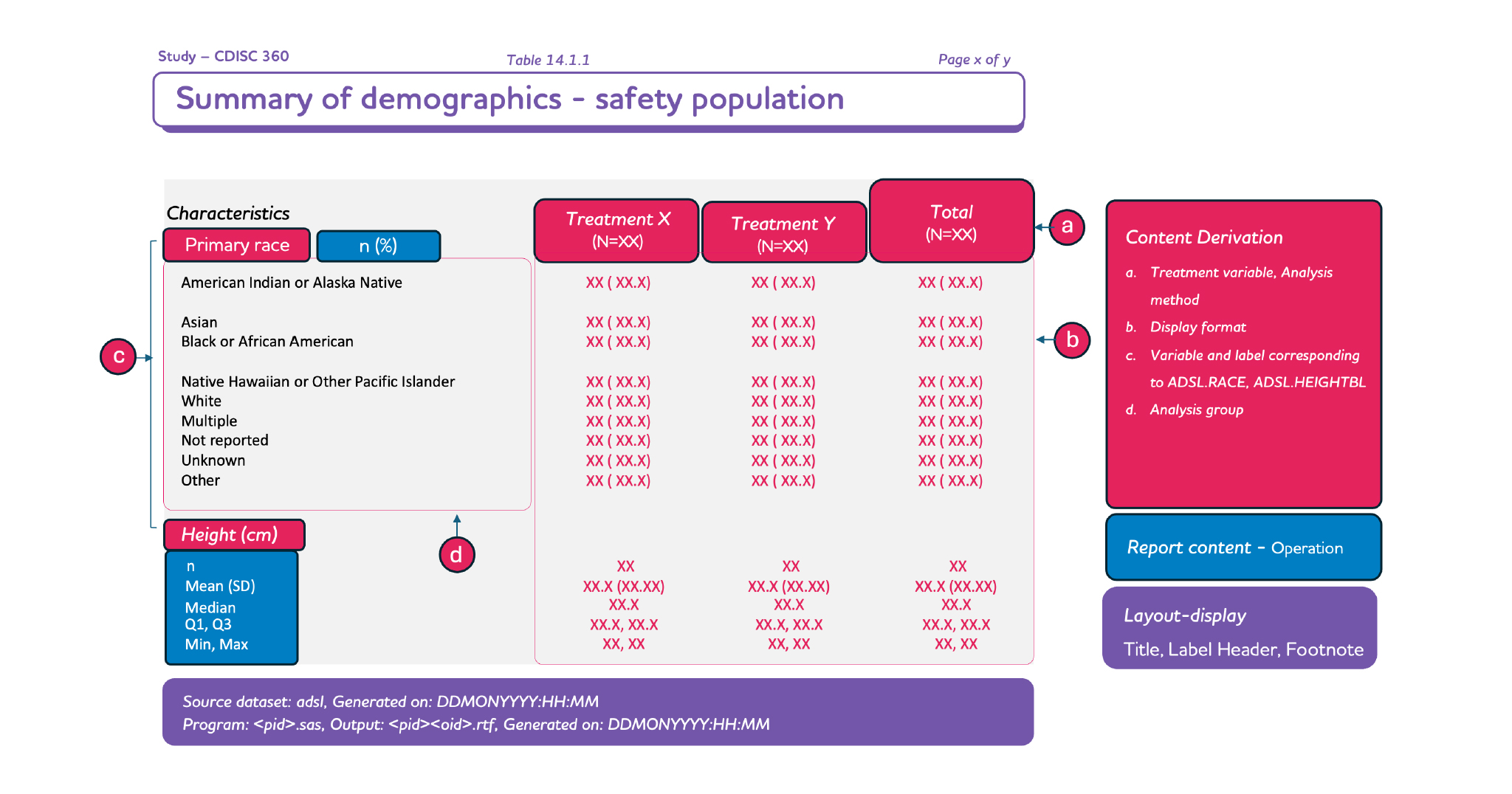

For any clinical study, the entire package of clinical trials will primarily consist of standard reports and study-specific reports. The design and layout of standard reports would remain the same and would not require additional work (such as generating and validating the standard reports). However, if there is any “study-specific” update in the standard report, it would be mentioned in the specification document which needs to be incorporated by the study programmer. We, therefore, can conclude that the standard report design can be reused for each study after some minor modifications defined by the sponsor at the study level.

However, the study-specific reports must be designed and currently, they are being designed. These are being maintained in documents or even designed on slides and pasted into the document. Lack of automation between specification and deliverable is one of the reasons for the gaps that are observed in reports during submission. Also, such a lapse is noted in later stages where some amount of clinical trial data is available.

Creating clinical trial report (CTR)

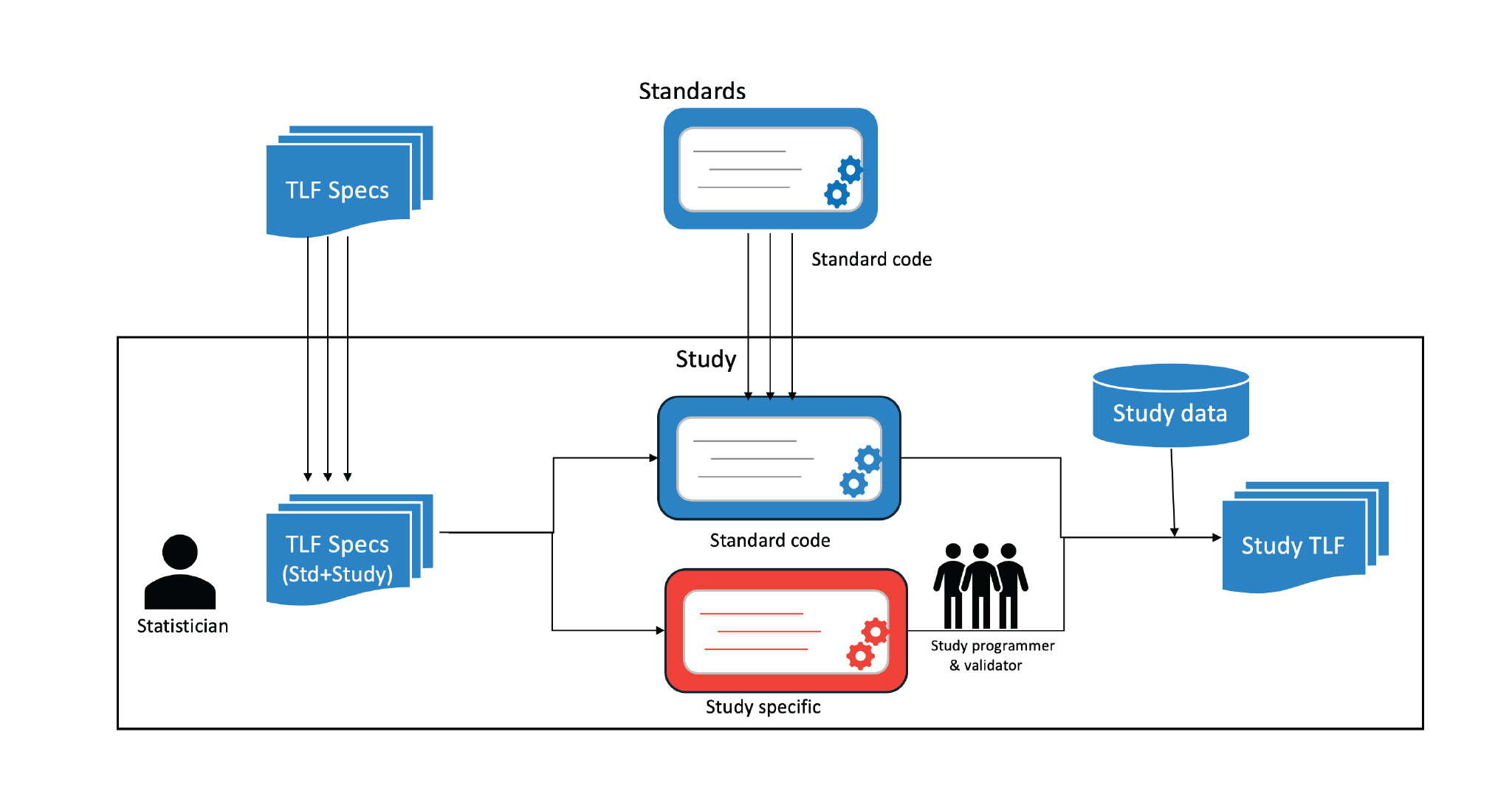

As mentioned earlier, the study programmer is the link between the specification and TLFs that are created. Currently, the process flow is depicted in Figure 1, where the trial statistician lists the TLFs (either from standard or study-specific) in the TLF specification document. This is then taken as input by the study programmers (including validators) who then create the codes needed to generate the TLF. These codes could also be a part of a standard library in some cases. Hence, every update that happens in the specification is cascaded through the programmer to see the intended impact in the TLF. This does have its own disadvantages. Other than the lapses and errors caused due to misunderstanding of the specifications, this also requires complete flow understanding for new programmers. Hence, new resources cannot be aligned during milestone deliveries.

In short, the TLF process can easily be optimized further to reduce the time and effort of the team. It can be summarized as follows:

The specification should be consistent and machine-readable.

Based on the specifications that are defined, the layout of the TLF should be easy to comprehend. The meaning and implication should be consistent to decrease the learning curve.

Lastly, the specification should be in a format that can be consumed by an engine for generating the TLF automatically.

All the above goals will not only reduce team efforts but also reduce the gap between the design and the actual report. However, to achieve this, we need to have robust data models which can cover all aspects of clinical trial reporting.